|

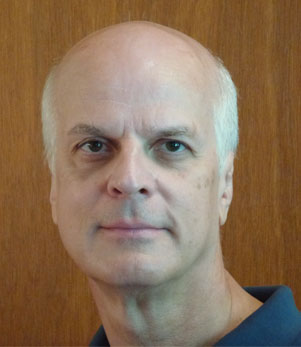

GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER 2011 John C. Lindsay Award Winner |

|

"Titan's Dynamic Atmosphere"

Planetary atmospheres

are complex systems. Studies of extraterrestrial

atmospheres have drawn on the much more extensive data and

analysis of Earth, but its atmosphere is only one

realization in the range of possibilities. Efforts

to understand other atmospheres and predict their behavior

must be closely tied to observations. The

atmospheres in the solar system are large-scale natural

laboratories with different “external” drivers (e.g.,

planetary rotation, solar forcing, internal heat

fluxes). Examining their response to these different

conditions is an important step toward understanding the

physical processes that govern them.

This talk focuses on one such laboratory, Saturn’s giant

moon Titan, which has been explored through

Cassini-Huygens and earlier Voyager spacecraft

measurements, as well as from ground-based

observations. Titan’s atmosphere is an intriguing

blend in the planetary line-up. In several respects,

it resembles Earth’s. Its atmosphere is primarily

N2, and its surface pressure is about 50% larger.

The second most abundant constituent is not O2 but CH4,

and there is evidence for a hydrological cycle involving

CH4. Titan’s winter stratosphere has different

chemistry than on Earth, but it has an analog to the ozone

hole, with strong circumpolar winds, condensate ices, and

anomalous concentrations of organic gases near the

pole. However, Titan is a much slower rotator than

Earth: its “day” is 15.95 Earth days. In this

regard, it is more like Venus, another slow rotator, and

it provides the second example in the solar system of an

atmosphere with global super-rotation, i.e., its winds

whip around the body in much less time than a Titan

day. Because of Saturn’s large axial tilt relative

to its orbital plane, Titan is a Venus with seasons.

The origin and maintenance of the strong winds on Venus

and Titan are poorly understood, and the seasonal changes

in Titan’s winds and temperatures—observations from the

Cassini spacecraft are already showing them—provide clues

for understanding these systems.